Hands erase Black history, from the Civil Rights Movement to Intersectionality on a school whiteboard.

U.S Legislation Erases African-American Students’ Histories

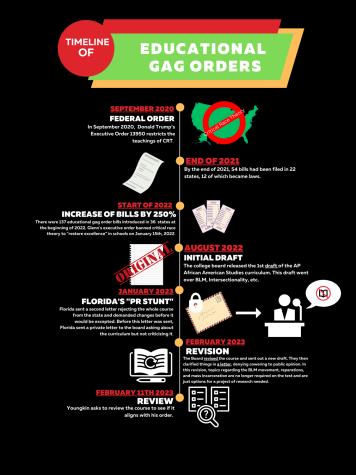

From Florida's restriction of the College Board's AP African American History course, to Virginia's decision to revise their curriculum, schools intentionally dilute and constrict African-American history and literature.

There are 42 states with legislation against so called “divisive concepts” such as critical race theory, and any discussion of gender identity, sexual orientation, sexism, or racism in their education.

Sixteen states have successfully restricted what they label as divisive concepts, 20 states are considering banning them, and six states have tried to ban them but failed. Only eight states have no restrictions or legislation against these concepts.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s national recognition sky-rocketed for removing the College Board’s AP African-American History course from the state of Florida. Now, Virginia Department of Education is reviewing and testing what is being taught in their K-12 curriculum.

A draft of the AP African-American course was released last year in August. Before publicly rejecting the course through a letter in January of this year, Florida sent a private letter to the College Board. The Florida Department of Education (FDOE) never brought up their claims of controversial influence like they did in their public statements in this letter.

Governor DeSantis said the course violates the Stop WOKE Act and Florida issued a state chart highlighting the topics they had their concerns for. These topics include Black feminism, Black queer studies, intersectionality, and activism.

This situation received increased publicity when the College Board published a revised framework for the course on the first day of Black History Month. The board removed many writers and scholars associated with critical race theory, the queer experience, and Black feminism, including Bell Hooks, who uses the phrase “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” and Kimberle Crenshaw, the founder of intersectionality.

Political indoctrination has no place in [Virginia’s] classrooms.

— Governor Glenn Youngkin

However, the Virginia curriculum is already censored enough as it is. There are only two Black authors in the English 11 curriculum and only two female authors out of 17 books in total.

“With literature, what we learn about is the struggle; Rosa Parks, how she struggled, slavery, how slaves struggle, but we never talked about the come up or the progress. How have we evolved since then?”An English 11 teacher, Mrs. Letter Word* commented.

Teaching only the victimization of Black History doesn’t share the full story.

Business and Personal Finance teacher Tiffani Vasquez would also prefer that Black History be incorporated into the curriculum, as well as touch on the positivity in the Black community. “There should be other things you know, we’ve got scientists, we’ve got historians, we’ve got poets, we’ve got leaders that are outside of Civil Rights that should be focused on as well.”

Youngkin also stated that “topics such as CRT construct students to look at life through race, gender, and sexuality,” and that they perpetuate the idea that “some students are consciously or unconsciously racist, sexist, or oppressive.”

Students from the African-American History class were asked if they viewed their peers negatively after taking the class, and only two out of the seven interviewed said yes. “I noticed how deeply ingrained racism is in society,” Mark Green* commented.

This shows the reality of the situation; rather than students viewing their peers negatively, they’re instead noticing the negativity around them, and this isn’t a new issue.

Vasquez remembers being a minority in her own history classes in high school. “It makes kids feel awkward too, especially if you’re the only person of color in a room, all eyes are on you. I dealt with that when I was in school for sure,” she said.

This, tied with the fact that Black history/figures are only taught in three out of the 13-grade curriculum, continues to paint American History in a biased light.

“Because as history is presented, it’s the white man came and made this beautiful America. They don’t really like to point out the bad things, they just want to see themselves as the Savior,” Word* believes.

Earnest Robinson, a Disabled Veterans Outreach Program Specialist who also works as an Activist, reveals that, “Even back in slavery, there were passages within the Bible that were removed because they would have potentially empowered the enslaved to revolt. It’s history being retold in a way that makes it more palatable.” Even back in slavery, there were passages within the Bible that were removed because they would have potentially empowered the enslaved to revolt. It’s history being retold in a way that makes it more palatable. — Earnest Robinson

Though the intentions of these legislators are good, the option of wanting to learn more should be open. Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and slavery aren’t the only aspects that played a part in the evolution of Black history.

Black history is in many places, and the purpose of this course that the Board introduced is “interdisciplinary” and reaches a variety of those fields “to explore the vital contributions and experiences of African-Americans.”

In the College Board’s letter, they apologized to Black scholars everywhere for not speaking up when Florida, who said the course lacked any educational value, criticized the course.

As for Virginia’s standard high school classes, there is an African-American History elective that grades 10-12 can take. However, because it’s an elective, it still limits the number of students that can learn more about their history.

“Us having to take this class [African-American History] to learn about Black history in general, It’s kind of like we have to go out of our way to learn about our culture and everybody that like has done so much for society,” Jasmine Hosea* criticized.

Something to realize about Black history is that it is American history.

“It’s long overdue that African-American history is taught. I think that African-American history is American history, and we live in America. So to understand our history, we need to understand African-American history,” said Mr. Nicholas Kwatnoski, the African-American history teacher.

Without the inclusion of important Black figures in the curriculum, many students are not taught about the people who founded the principles of Black culture.

For instance, 14 students in the school were interviewed and asked to name five black figures besides Dr. King and Rosa Parks. Out of the seven students in African-American History, only two were able to name five, and of the seven who take standard History classes, none were able to, questioning their education.

“It narrowed my view of what really happened. Like, I don’t know anybody who played a big role other than Martin Luther King Jr.,” Sara Rancover* says.

Not going into detail about more defining events and topics in Black history like the March on Washington and Bus Boycotts, taints history with idealism. We learn about big changes in Black history, but only if they came from the most known activists, Rosa Parks and Dr. King.

In Virginia, the restrictions put on by Governor Youngkin closes the door on any discussions of “divisive concepts,” all of which are very broad ideas. This leaves black history too basic in its teaching.

However, the African-American History class seems to be inclusive and dives deep into the richness of Black histories, such as Black business’, the role of the Black church, The Black Panther Party, and other uplifting events/figures.

“This class has opened my eyes and showed all of us that there are other people that definitely made a significant impact on African-Americans,” student Michael Saintclair* said.

These restrictions within the bills will destroy Black history in America. Students aren’t getting the full story about the history they do learn because there aren’t openings for opportunities to have discussions about Black history.

*Some names have been changed to remain anonymous due to privacy concerns.